Newly Identified Dinosaur Grew a Giant Back Sail Just to Have Sex

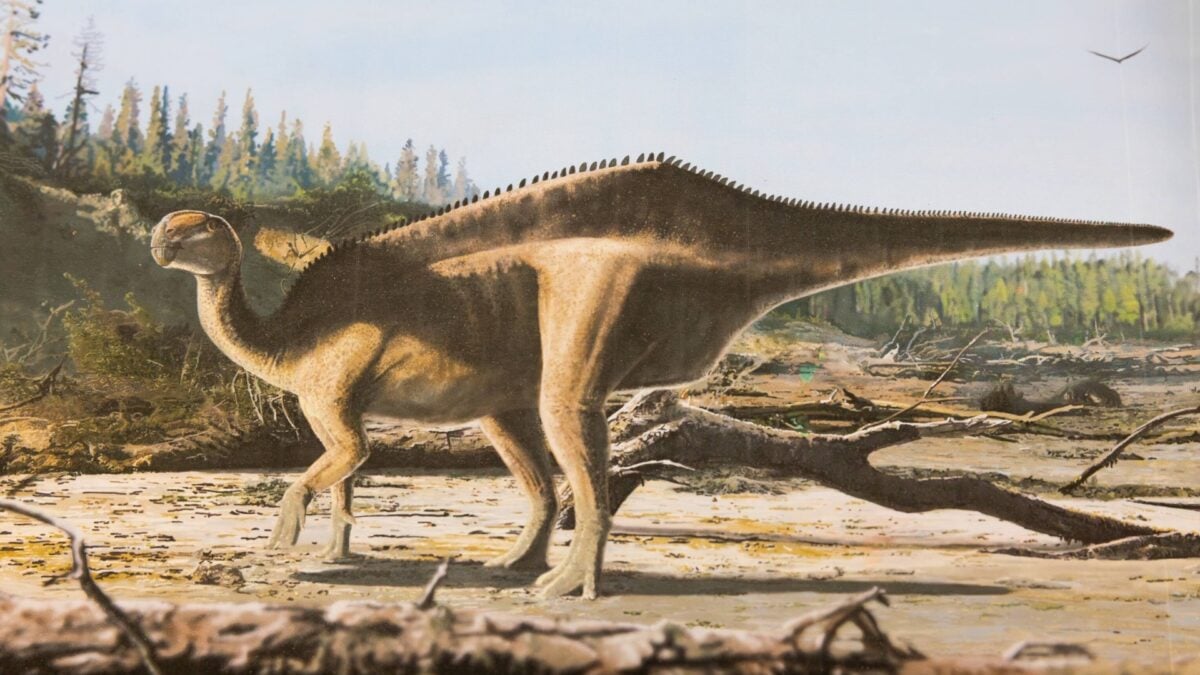

Paleontologists have identified a new type of iguanodontian dinosaur in England—and these dinos have some of the coolest back fins we’ve ever seen.

Like many recent discoveries, researchers “discovered” Istiorachis macarthurae after re-examining previously excavated fossils. The species is named after a famous sailor from the Isle of Wight, where the fossil, dated to around 125 million years old, was originally found.

After inspecting the fossil more closely, paleontologist Jeremy Lockwood and his colleagues came to the realization that they were looking at a completely different kind of dinosaur. Previously, researchers believed these bones belonged to one of the two known iguanodontian species from the Isle of Wight. The results of this investigation were published on August 21 in Papers in Palaeontology.

“While the skeleton wasn’t as complete as some of the others that have been found, no one had really taken a close look at these bones before,” said Lockwood in a release from the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom. “It was thought to be just another specimen of one of the existing species, but this one had particularly long neural spines, which was very unusual.”

Taking a closer look, Lockwood realized that these elongated spines weren’t a random quirk of this particular individual but features that belonged to a different species. To confirm his suspicions, Lockwood and his colleagues performed a detailed investigation into the fossil, creating a large database of dinosaurs with similar physical characteristics. As a result, they were able to identify broader evolutionary trends in dinosaurs with sail-like body parts.

Paleontologists aren’t exactly sure what these sails were used for, but they have some guesses. Existing theories range from body heat regulation to fat storage, but in the case of Istiorachis, the most probable answer is that the sails evolved in male species to “impress mates or intimidate rivals,” Lockwood explained.

“Evolution sometimes seems to favor the extravagant over the practical,” he said. “Istiorachis‘s spines weren’t just tall—they were more exaggerated than is usual in Iguanodon-like dinosaurs, which is exactly the kind of trait you’d expect to evolve through sexual selection.”

Istiorachis‘s sails also confirm a research trend that suggests such elongated spines in iguanodontians began in the Late Jurassic period, or about 143 to 162 million years ago. Paleontologists are especially interested in spotting a case of “true” hyper-elongation, where “spines stretch to more than four times the height of the vertebral body,” according to the statement. Istiorachis, while impressive, hasn’t quite reached that level of extravagance, the paper suggests.

Investigating the past also uncovers some insights into the present—and perhaps vice versa. For instance, several species of living reptiles today harbor similar, elaborate crests and sails that signal health and strength to potential mates, Lockwood said, adding, “Istiorachis is a deep-time example of the same evolutionary pressures we see shaping display structures in modern animals.”

- CỘNG ĐỒNG

- News

- Tech

- Food

- Causes

- Personal

- Art

- Crafts

- Dance

- Drinks

- Film

- Fitness

- Giochi

- Gardening

- Health

- Home

- Literature

- Science

- Networking

- Party

- Religion

- Fashion

- Sports

- Stars

- Xã Hội